In an age marked by uncertainty and cascading disruption, strategic foresight offers something essential. Among its most potent tools, scenarios offer something uniquely powerful: not a prediction machine, but a perception-shifting process. Scenarios don’t tell us what will happen; they change how we see. When done well, they function like a kind of cognitive psychedelic—dissolving default assumptions, unsettling the familiar, and revealing overlooked possibilities latent in the present. This post explores why scenarios are at the heart of my foresight practice—not simply to prepare for multiple futures, but to cultivate the kind of perceptual shift that allows individuals and organisations to widen their understanding about what’s possible, and to think, feel, and act differently in the face of radical uncertainty.

Our future selves as strangers

Shortsighted decisions result in part from a failure to fully imagine the subjective experience of oneʼs future self.

— Jason Mitchell

Long-term thinking doesn’t come easily to most people. We are wired for immediacy. While we can easily picture tomorrow or next week, our capacity to imagine 10-, 20-, or 50-year futures is limited. Anyone involved in public policy or corporate strategy will have observed this tendency firsthand: a growing bias toward short-termism, reactionary decision-making, and a reluctance to invest in actions whose benefits may not materialise for years.

How can we make sense of this?

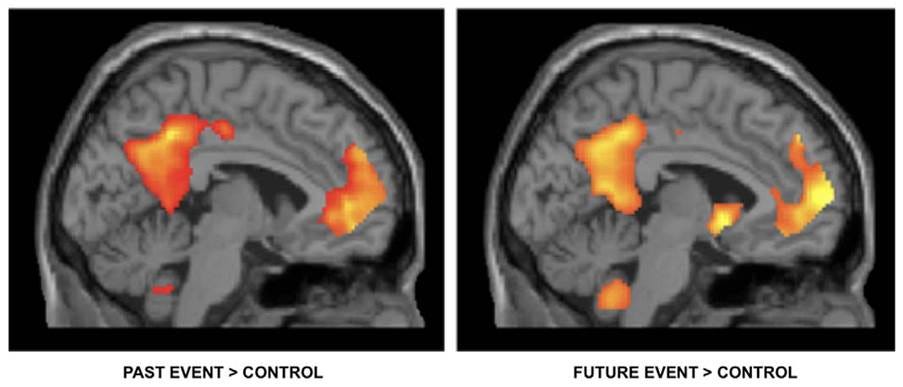

Neuroscience offers some insight. Research has shown that when we imagine our future selves—whether a year or a decade ahead—our brains respond as though we are thinking about another person entirely. When we think about the distant future, the medial prefrontal cortex, associated with self-related thinking, shows reduced activation. In effect, the brain treats the future self as a stranger—someone we don’t really know—or care about. We can see this dynamic at play in the every-day with decisions about what we eat. Each time we choose to gorge on highly processed sugary foods, our rational mind knows it’s not good for our future self. But that future self feels distant from us, like someone whose interests and welfare are not our own.

In one study, Hal Hershfield and colleagues found that people exhibit lower emotional engagement when considering their future selves. Jason Mitchell’s research further demonstrated that this reduced activation in self-referential brain regions contributes to intertemporal choice errors. Simply put: we struggle to make good decisions for the long-term because the future feels abstract and disconnected from our present sense of self.

The error of linear thinking

Any useful statement about the future should at first seem ridiculous.

— Jim Dator, Director, Hawaii Research Center for Futures Studies

Compounding the challenge to think well about the future, we also have a bias toward viewing the future as a linear extrapolation of the present. In the absence of a vivid mental picture of the future, we tend to rely on the cognitive shortcut of assuming that tomorrow will more or less resemble yesterday. And there’s a good reason for that. The part of the brain we use to think about the future is the same one we use to remember the past. This mechanism makes us prone to what might be called "temporal inertia"—a failure to appreciate how different the future might actually be from the present.

Is it a safe bet to think the future will be anything like the past? History suggests otherwise. Over the past two decades alone, events with disproportionate impacts have emerged seemingly out of nowhere: global pandemics, financial crises, populist uprisings, extreme weather events, and technological leaps. These so-called "black swans" and "grey swans"—low-probability, high-impact events—are not as rare as we might think. A geneticist friend once observed that while specific genetic diseases are rare if taken individually, rare genetic diseases as a category are surprisingly common. The same holds true for disruptive futures. They litter every decade of history.

Consider a few examples. The September 11 attacks in 2001 upended global security assumptions and ushered in a new era of counterterrorism policy and surveillance. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008 sent shockwaves through economies worldwide, exposing systemic fragilities that few had anticipated. The Arab Spring in 2010–2012 unleashed a wave of political upheaval across the Middle East and North Africa, challenging entrenched regimes and redrawing geopolitical alliances. The election of Donald Trump and the rise of populism seems to have foreshadowed a re-shaping of the world’s geopolitical order. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 disrupted global health systems, supply chains, and social norms, while simultaneously accelerating the digital transformation of work and the workforce globally. More recently, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 shattered long-held assumptions about European security and global energy markets. And the rise of large-scale generative AI in 2023 has rapidly redefined the boundaries of knowledge work, automation, and disinformation.

In addition to these headline-grabbing events, we have witnessed increasingly frequent climate-related disasters: catastrophic bushfires, floods, and heatwaves that exceed historical baselines and render previous planning models obsolete. Many of these were not unimaginable in advance, but they were often discounted or excluded from decision-making frameworks because our brains seem more geared to planning for the mean rather than the exception. And yet, if we take the long view, the cumulative probability of disruption in one form or another is high, and the strategic impact is often immense. Across history, disruption is the norm rather than the exception. The precise nature of the disruption might be unknown, but disruption itself is a near certainty.

Scenarios as future memory

In our times of rapid change and discontinuity, crises of perception—the inability to see a novel reality emerging by being locked inside obsolete assumptions—have become the main cause of strategic failures.

— Thomas Chermack, Using Scenarios

This is where scenario planning plays its most vital role. It acknowledges our cognitive limitations and then seeks to work with them. Since we use memory to construct our sense of the future, working with scenarios functions as a way to deliberately build ‘future memory’. As a kind of simulation, scenarios function as a low-risk proxy for real life experience itself. Within a safe sandbox, they can seed the imagination with vivid, alternative futures, expanding the library of stories we have available to reflect on when a moment of surprising novelty – be it a shock or delight – arrives in our world.

Good scenario work is about perception, not prediction.1 As a foresight technique, the use of scenarios aims to perform a kind of strategic time travel in order to shift perception about the latent possibilities of the present moment and generate mental preparedness. Well-constructed, immersive scenarios built on a sound analysis of current and emerging trends as well as weak signals of change observable in the present help to widen our perception about what’s possible. Through an exploration of the multiple ways in which these trends and signals may unfurl and converge, scenarios serve to train us to be more attuned to the ‘evolutionary potential of the present’, as complexity thinker Dave Snowden calls it. Snowden argues, correctly in my view, that foresight practice at its best when it focuses us more on the present than the future. Though a complexity science lens, he highlights that the advantage of the present is that it is knowable, unlike the future which is unknowable. It is the present rather than the future that is the locus of our agency:

‘[T]here are a range of possibilities available, which are adjacent to the present. At any given point in time, a system may re-orientate itself to possibilities that are adjacent to current reality, but not those which are distant from it. Not all such adjacencies are obvious.’

Indeed, those adjacencies can be hard to see. This is where scenarios, used not for predictive power, but instead as a tool for deep exploration and perception-shifting, are most useful. By priming us to see the future as different from today, they invite us to reckon with how such futures emerged, and in doing so they afford us heightened sensitivity to notice weak signals of change as they are emerging in the present, to make sense of emerging patterns, and in turn to act earlier than we otherwise might. It enables us to see more of the dance that is underway, and to consciously enter into it. In doing so, it shifts not only what we think, but how we think and feel about the future—and, crucially, how we might creatively use our agency given the constraints and affordances of the present (again, a hat tip to Snowden).

Jane McGonigal from the Institute for the Future has explained these benefits before in talking about the results of the 2008 IFTF-led scenarios project called Superstruct, a large-scale distributed scenario exercise involving nearly 20,000 people which explored a respiratory pandemic scenario.

‘McGonigal asked them to simulate a respiratory pandemic that originates in China in 2020 and travels around the world infecting millions of people. They practiced wearing masks in public. They wrote journal entries about how it feels to get quarantine orders. And they figured out how they’d use their unique skills to help others in this scenario.’

In working with those scenarios, participants anticipated – correctly, as the COVID-19 pandemic proved – a range of phenomena, including lockdowns and resistance to such measures, a mass exodus of women from workforce (who disproportionately shouldered responsibility for home-schooling), the proliferation of misinformation and conspiracy, the rise of anti-mask sentiment.

A decade later, people who had participated in the scenario exercise reported a level of psychological preparation for the real pandemic because they had already ‘rehearsed the future’.

‘[W]hen the real respiratory pandemic originated in China in 2020, they felt ready. They emailed McGonigal things like, “I’m not freaking out, I already worked through the panic and anxiety when we imagined it 10 years ago,” and, “Time to start social distancing!”’

By taking an extended wander through multiple futures, participants were able to vividly explore the minutiae of those worlds in sometimes unsettling or delightful detail. And this is by design. It’s precisely the personal sense of being unsettled or delighted through exploration of the vivid details of a future world that produces a shift in perception that allows for a reimagining of what’s possible. Participants imagine what could be, only to find that seeds of that very future already exist in the here and now. Suddenly, what had been unthinkable becomes thinkable. What was far-fetched is reperceived as an adjacent possible, which was barely a hop, skip and a jump away from the present moment. As they emerge from a scenario exercise, people perceive with new clarity the evolutionary potential of the present, and with it, a new sense of their own agency as stewards of that potential.

By way of example, let me explain. A couple of years ago I ran an immersive scenario-like workshop with a government organisation responsible for, among other things, early childhood learning and aged care. Their task in the workshop was to imagine a range of strange or impossible futures, future conditions they thought would be unthinkable in the present moment. One group’s exploration converged on a new integrated model of early learning, child care and aged care which saw both old and young within the same facilities. They called it ‘Integrated Intergenerational Care’, imagining a new service that promoted intergenerational connections across age groups, meeting care needs while fostering social connection and intergenerational learning. I watched as the group excitedly built out their ideas, strategically time travelling into an alternate realm via their collective imagination, exploring the implication of that future, and making the journey from cynics to believers.

The most powerful moment came when they were asked whether their imagined service was actually feasible in reality. Inconceivable, they thought. Current day services were segregated and siloed in nature, and heavily regulated in this manner, the assumption being that this set of conditions made their imagined future an unlikely evolution. Then they were asked to scan around the global landscape to see if this concept had been floated anywhere in the world. To their astonishment, it had not only been floated, but the first such intergenerational care facility in their own state – a kindergarten situated alongside an aged care facility that allowed young children and older residents to come together for activities – was being built just a fifty minute drive from where they were sitting. Suddenly the impossible was rendered possible. The scenario exercise served to remove the blinders that had been preventing them from seeing what was already emerging right near them.

Scenarios as psychedelic intervention

As the twenty-first century unfolds, it is becoming more and more evident that the major problems of our time – energy, the environment, climate change, food security, financial security – cannot be understood in isolation. They are systemic problems, which means that they are all interconnected and interdependent. Ultimately, these problems must be seen as just different facets of one single crisis, which is largely a crisis of perception.

― Fritjof Capra, The Systems View of Life: A Unifying Vision

The perceptual shift is not merely a nice-to-have side effect of the scenario process ― it is the most important outcome. Sure, scenarios are undoubtedly useful as a planning tool, enabling options testing and wind tunnelling of strategies within alternate futures. However, as the IFTF and intergenerational care example illustrated, the higher order outcome is that it widened participant perception of what they believed to be possible, or even probable, not just in the future, but in the here and now. When conditions are genuinely reperceived, its leads to new beliefs, and new beliefs beget new goals, new rules, new culture, and even new power structures. Legendary systems thinker Donella Meadows argued that the most effective point to intervene in a system was not to change positive feedback loops or its rules or even power dynamics, but rather, the highest leverage could be found in ‘the mindset or paradigm out of which the system arises’.

Paradigm shifts arise from a shift in perception. Think of the health crisis or near-death experience that catalyses a dramatic reperceiving of values, reprioritisation of time and relationships, and a re-evaluation of what constitutes a meaningful life. Or the sudden loss of a job that unmasks the fragility of identity built on career while opening up new possibilities for identity. Or the birth of a child, which can dissolve one’s sense of ‘self’ and the limits of care. Or the psychedelic trip that ushers the traveller through a rollercoaster of overwhelming awe, white-knuckle terror and transcendence, and then dissolves their fears, including a fear of death in terminally ill patients. To some extent, good foresight should function a little like a psychedelic trip, temporarily downregulating the Default Mode Network of the brain, dissolving habitual patterns of thought and enabling new connections, perceptions, and cognitive flexibility to take shape.2

Each of these life-altering events doesn't create new values out of nothing—they reveal what was already present but unseen, altering the lens through which the world is interpreted. Strategic foresight should perform a similar function for decision makers. Using tools and methods like scenarios stands a chance to do exactly this. Where an organisation’s “default mode” is its habitual ways of seeing, interpreting, and responding to the world—its entrenched assumptions, strategic routines, and mental models—the use of tools and processes like scenarios seeks to deliberately interrupt this pattern. They introduces ambiguity, multiplicity, and estrangement from the present, weakening the dominance of a singular “official future.” Immersed in scenarios, participants are invited to reperceive the present and see it with fresh eyes, to see more of what there is to be seen. And at some point, any genuine change at the level of perception cannot help but cascade through the system, its goals, power structures, rules, and its culture.

Corporate confectionery vs the experiential

I’ve produced and deployed more than a few trend reports over the years. Trend reports are fine. They can serve a role, but in my experience, trend reports are like corporate confectionery. They're sweet, easy to digest, and everyone enjoys them in the moment—but they rarely offer the substance needed to nourish us in the long term. They get metabolised quickly, give a brief sugar rush of insight, and then fade away without leaving much behind, having failed to shift the conversation, let alone the decision.

Throughout my career, I have leaned heavy on the kind of rigorous structured analytical methodologies that underpin most trend reports. My bread and butter was using structured analytical methodologies to create robust evidence-based assessments about the future for the best part of a decade. Yet in my experience, I’ve rarely observed a trend report or situation assessment trigger a genuine shift in a decision-makers’ paradigm. I have, however, seen scenarios do that. Again and again. This may be because trend reports, which are often robust, well-researched and heavily referenced, speak almost exclusively to the intellect. This seems a perfectly acceptable situation if you think that, as many “rational” people do, it is the intellect alone that occupies the role of decision maker within each individual. However, it turns out that this isn’t the case. Neuroscience has demonstrated that the intellect shares this role: both head and heart at the helm.

Neuroscientist Antonio Damasio demonstrated in one famous experiment that as much as we like to think we make decisions purely rationally, the choices of even the most rational among us are shaped heavily by our emotions. Damasio’s experiment involved patients who had damage to the parts of their brains that connect emotion with reasoning, particularly the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. These individuals could logically analyse choices and list pros and cons, but they struggled to actually make decisions—even simple ones like choosing a lunch option or scheduling an appointment. The core finding was that without access to emotional input, they became trapped in endless deliberation. Damasio concluded that emotions are essential for decision-making because they help us assign value and significance to different options, guiding us toward action. Reason matters, of course, but it turns out that it neither happens in a vacuum nor has the last word. That’s just not how the human creature works. Rational analysis, in the absence of emotional data, is insufficient.

This insight has major implications for how we do foresight. If we want foresight to override the default mode and crack open perception, then we must engage more than just the analytical mind. Trend reports, data, and models have their place, but they don't reach deep enough into the complex and multifaceted cognitive loops that influence how we see and what we choose. To generate the kind of perceptual shift that allows us to see novelty in the present and use our agency more wisely to co-create better futures, then we need to engage the emotional and imaginative faculties—not just sit around a table exchanging rational propositions, but create processes and rituals that stir feeling and awaken new ways of seeing.

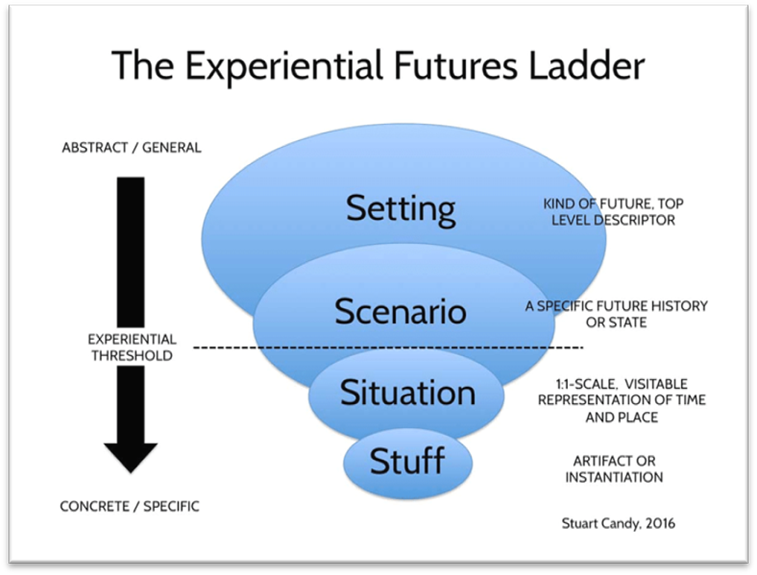

The difference with scenarios, particularly those that invite people into a participatory, multi-sensory process, is that they sit on the threshold between the abstract and the concrete, between that which feeds the intellect and that which stimulates whole-body cognition. Professor Elke Weber, a cognitive psychologist, has shown that experiential modes of exploring the future exert a stronger influence over decisions made under conditions of risk and uncertainty than abstract, descriptive methods. Indeed, scenarios tend to work best when they cross into the experiential realm, when they are relayed to participants through immersive audio theatre that don’t convey mere clinical facts about a speculative future world, but instead the visceral day-today experiences of its fictitious inhabitants.

Scenarios have even more power when such narratives form the substrate of an interactive game or simulation in which there are objects from that imagined future that can be held and manipulated, where the stakes are clear and where choices have consequences. All of these elements engage the intellect, but they also reach into the brain, down the brainstem and through the Vagus nerve they engage our heart and gut. And so they should, because we don’t merely think our way to our choices, we feel our way to them, too.

When we deeply engage in scenario work—through immersive narratives, artefacts from the future, or lived personas—we are not just reasoning our way into the future. We are building emotional familiarity with that terrain. We start to internalise it, literally encode it within our bodies, and in doing so we create future memories, allowing us to recognise early signals and respond faster when those futures begin to materialise.

“Now I can see a way forward”

Years ago, I ran a scenarios workshop with a group of senior organisational leaders. Before diving in, they were immersed in vivid audio narratives—each one a journey into a different future shaped by climate change. Some scenarios were bleak, others more hopeful, but all made the consequences tangible: changes to daily life, work, food, family. When the session ended, one participant paused and said:

"I know a lot about climate change. I've been studying it for decades. But it wasn't until I listened to these scenarios that I could really imagine what my child's life might actually be like. And now I can see a way forward."

That moment illustrated something essential. Scenarios work because we are storytelling creatures. We don't just think about the future—we feel it when it’s brought to life through narrative. Stories help us ‘see’ the world. We do not merely see what is there to be seen—we see what we are primed to see.

Scenarios are structured acts of imagination that help us tell new stories. Done well, they stir empathy, challenge assumptions, and stretch our sense of possibility. They’re mirrors that reveal blind spots. Maps that reveal unfamiliar terrain. Rehearsal spaces for choices not yet made. And yes—sometimes they’re a bit like an LSD trip, expanding the boundaries of what we thought was real or relevant.

Scenarios won’t tell us what will happen. But they can ready us—emotionally, psychologically, strategically—for whatever might.

I’ll leave you with this final provocation:

Imagine someone you trusted told you that there was an invisible layer of reality that was located right in front of you, another dimension of sorts—one from which many of the greatest forces to shape your life or your organisation, for both better and worse, had and will continue to originate. Then they told you that with the right rituals, you could learn to glimpse that which was hidden.

Would you want to learn to see it?

Would you want to take up your role as a steward of the evolutionary potential of the present?

It’s important to draw a distinction between foresight and forecasting. They are two related but fundamentally different disciplines. Put simply, forecasting projects the most likely future from current data, while foresight explores a range of plausible futures to guide strategic choices. Forecasting is useful in domains of high certainty, foresight is most useful when persistent uncertainty prevails. Where we have the luxury of good data from which we can confidently extrapolate, then forecasting is the tool of choice. But if our data is poor, or our domain too complex and multivariate, then foresight should be the go-to.

From a neuroscience perspective, there’s a network of interconnected brain regions called the Default Mode Network (DMN), which is the brain’s “background processor” for the inner world—handling memory, identity, imagination, and self-reflection. It plays a central role in how we construct a sense of self and continuity over time. The DMN is active when we imagine future events or replay past experiences. Psychedelics are known to temporarily downregulate the DMN, dissolving habitual patterns of thought and enabling new connections, perceptions, and cognitive flexibility. In his book, How to change your mind, Michael Pollan quotes Mendel Kaelen, a Dutch postdoc studying psychedelics, who explained the effect of psychedelics on the DMN: "Think of the brain as a hill covered in snow, and thoughts as sleds gliding down that hill. As one sled after another goes down the hill, a small number of main trails will appear in the snow. And every time a new sled goes down, it will be drawn into the preexisting trails, almost like a magnet." Those main trails represent the most well-travelled neural connections in your brain, many of them passing through the default mode network. "In time, it become more and more difficult to glide down the hill on any other path or in a different direction. "Think of psychedelics as temporarily flattening the snow. The deeply worn trails disappear, and suddenly the sled can go in other directions, exploring new landscapes and, literally, creating new pathways." When the snow is freshest, the mind is most impressionable, and the slightest nudge-whether from a song or an intention or a therapists' suggestion- can powerfully influence its future course. (p.384)

Great article! I've been hearing from a couple of places lately an increased skepticism about scenarios. The biggest concern is that an organization might find it a reputation liability to be attached to a non-official, and especially a dark, image of the future. For example, in today's environment something like your 2020 respiratory pandemic scenario risks being labeled "predictive programming". This is a good reminder why it's hard to get the benefits any other way.

Terrific James. Whilst there's a lot to digest in the post, your references to the human "imagination" are standing out for me. When you say, "Scenarios are structured acts of imagination that help us tell new stories", I am reminded by the writing and practice of John Paul Lederach in his book 'The Moral Imagination: The Art of Soul of Peacebuilding'. His lessons from the complexity and conflict that arises from Peacebuilding seems more relevant than ever in the world right now.

In the context of building peace, Lederarch defines the Moral Imagination as an artistic endeavour, "To imagine something rooted in the challenges of the real world yet capable of giving birth to that which does not yet exist." He sees the Moral Imagination as the source that gives real life and agency to constructive change. This requires a worldview shift, and he challenges his fellow peacebuilders to, "go well beyond a sideshow and lipservice to attain the art and soul of change". He has learned through experience that change requires both skill and art. I take from this that any sector facing complex-system challenges, actors must learn to envision their work as a creative act, more akin to the artistic endeavour than the technical process.

In my own experience of supporting change-makers, I've noticed how the creative, serendipitous moments - and not the technical and structured facilitated processes - that lead to the turning points and breakthroughs. Two of my old Reos Partners colleagues often tell a story about such a breakthrough. They were process guides for a state government, Premier lead taskforce designed to bring 3 stakeholder groups together who, for decades, had been at war. For months, the entrenched and unwavering views of participants remained stuck and little progress was made. But then one day, on a largely self-organised learning journey, one of the leaders announced an observation that arose for her during a paired walk, "When I began this process, I thought that 'we' were the only group losing. Now I'm realising that we are 'all' losing." In that moment, there was a discernible shift in the whole group. Tension fell away and participants began to open up and talk about the future. The pre condition here was a shared realisation that the current situation was intolerable and that imagining a different future was required.

But what 'system conditions' are needed to make these emergent breakthroughs possible? Lederarch again draws on his career in peacebuilding and asks this question, "What disciplines (or practices), if they were not present, would make peacebuilding impossible?" They are:

1. The Centrality of Relationships

2. The Practice of Paradoxical Curiosity

3. Provides spaces for creative acts

4. The Willingness to Risk

Combined, these simple disciplines form the conditions that make the moral imagination and peacebuilding possible. Lederarch observes, "that time and time again shifts in patterns were defined by the capacity of actors to imagine themselves in relationship, a willingness to embrace complexity and not frame their challenge as a dualistic polarity, acts of enormous creativity, and a willingness to risk." The results from these moments were the development of on-ground initiatives that created and sustained constructive change.

SO WHAT does all this Moral Imagination stuff have to do with scenarios and foresight? Here's a few things coming to mind:

1. We, as consultants or leaders, need to hold firm on the use of 'creative' and 'non-technical' processes and avoid the traps of "lip service and sideshows" that the system expects. We often bow to pressure of the "traditional" when the opposite is needed. From the example of my colleagues above, I think the creative or edgy sceanrio and foresight work is an easy sell when there is a burning platform for change, and when stakeholders know they can't make progress on their own.

2. When we do get opportunities, as process guides or facilitators, we learn to play with 'system conditions' in ways that can give rise to the unexpected and to the serendipitous moments of change and learning. That could be playing with simple things like talking in circle (rather than behind tables), going on walks, meeting on Country, drawing pictures rather than writing clever words.

3. The reality is we need to deploy BOTH/AND --> The technical/expert/data driven processes AND the creative/artistic methods. If we treat this balance as a Polarity, maybe its possible to create value from the upside of both poles?

This was more of a new post than a comment!!