AI & the flat-packing of the human experience

On intelligence, machine metaphors and human creativity.

Language can play tricks on us. Used imprecisely, it can cause us to conflate fundamentally different things. Take the word intelligence. For most English speakers it describes the ability to understand and solve complex problems. It’s a word we’ve typically reserved for organic entities, typically ourselves, in whom we have detected evidence of these faculties.

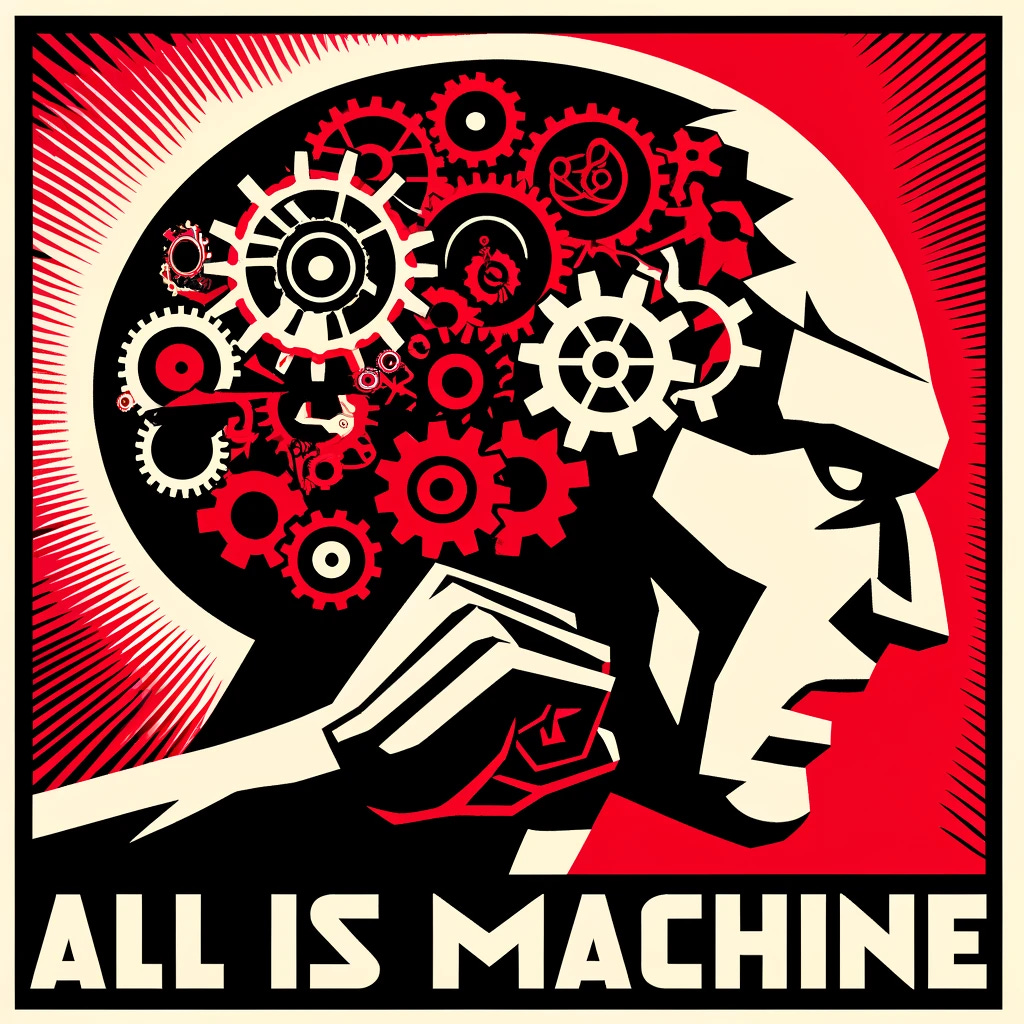

In 1955, however, computer scientist John McCarthy coined the phrase artificial intelligence in a research proposal paper to describe a vision of creating machines that could mimic human cognitive functions. The problem is that, by using the word intelligence to describe then only hypothetical capabilities of machines, McCarthy smuggled in some critically flawed assumptions that continue to haunt us.

The haunting is apparent today in much of the talk we hear about AI reaching "human levels of intelligence", and also in the fears about how many human thinkers and creators will be displaced from their roles in the near future. “What will be left for us to do?”, cry white-collar workers and creatives the world over. But I would argue that when we accept this framing for the conversation—that the gamut of human faculties are likely to be eclipsed by AI in the near term—we are unwittingly accepting a false, idiosyncratic and fundamentally reductionist conception of human intelligence (and by extension, the human creature itself).

Namely, the phrase that may lead us to that categorical error—artificial intelligence—was born of minds colonised by the myth of world-as-machine. It is a myth that has gripped the minds of many particularly since the advent of Newtonian physics which imagined the universe as a predictable, clockwork mechanism governed by mathematical laws. Similarly, Descartes and Hobbes both took a mechanistic view of the body, with the latter suggesting human thought could be understood as a form of complicated mechanical computation. And indeed, at the moment of its very inception, the founders of the field of AI took such assumptions as their starting point. The second sentence in McCarthy’s 1955 proposal paper could hardly have made the intellectual lineage of the fledgling discipline more explicit when it stated the following:

‘The study is to proceed on the basis of the conjecture that every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it.’

Today, the phrase artificial intelligence has become ubiquitous. Also hiding in plain sight is the significant intellectual baggage has also been smuggled into present day via the continued use of intelligence to describe the capabilities of these machines. Specifically, AI remains a faithful custodian of the myth of world-as-machine, and even human-as-machine. As evidenced by the range of predictions from prominent technologists proclaiming the imminent surpassing of human intelligence by AI, this myth and its reductionist tendencies still holds sway among the technological elite and their consumer acolytes. This continues despite the advances in physics in recent decades that draw the clockwork universe metaphor into question, and which should have also side-lined a reductionist perspective of human intelligence in favour of a more holistic, complex systems-based approach.*

Instead, the public discourse around AI seems to assume that the technology is developing rapidly along the same ontological track that human intelligence occupies, and indeed that it is rapidly sneaking up on the latter. In other words, it assumes that when we speak of the intelligence in artificial intelligence and the intelligence in human intelligence, we are talking about the same essential thing. And so it follows that if we think it’s the same thing, we’re also likely to feel that our jobs and creativity is at threat from AI.

The threat is real. But it is only real to the extent that we accept an impoverished notion of what human intelligence is, of what the human is, one that can only conceive of the human mind as complicated albeit replicable computation. As it relates to human creativity, the threat is only real to the extent that we accept an impoverished standard for creativity. And make no mistake, the industrialisation process has indeed successfully beige-ified some facets of human creativity, reducing them to repeatable and algorithmic production processes. Take popular music industry, for example. Anecdotally, we’ve heard many Boomers complain that “music isn’t what it used to be”. But a 2012 study actually demonstrated that since the 1950s Western popular music has become significantly more homogenous, reflecting a less diverse timbral palette and more restricted pitch variation across time. Mediocre as the music may have become, music industry executives have figured out the formula, how to consistently reproduce it, and sell it for a reliable margin. For these such industries, AI will undoubtedly be a threat.

Douglas Rushkoff gestured at something like this in a recent episode of his Team Human podcast, where he reflected on AI and the artistic endeavour:

‘AIs are fine for industry. They are a product of Industrial Age thinking. They reinforce the values of Industrial Age thinking. They do not create, they model... If AI is a threat, it’s more a threat to the creative industries than to creativity itself.’

In other words, wherever creativity has been co-opted by industrial forces—be it the music industry, Hollywood or other media—such industries and the creatives that inhabit them may indeed reasonably assume themselves to be at threat from recent advancements in generative AI technologies.

So, you might then think, "As a non-industrialised artist or creative, I’m still pretty safe then, right?". Well, that depends.

Firstly, it depends on whether we collectively accept a reductionist view of what it means to be human and intelligent. We’ll know we’ve accepted this view if we see an almost unrestrained willingness to outsource and automate our sensemaking and decision-making to AI as soon as it is claimed to match or exceed human performance levels. But remember, this shift won’t happen because AI consistently demonstrates excellence in creating moving imagery, narrative fiction, or music. More often, it will be because the industrial paradigm considers the outputs of AI to be consistently good enough given their lower costs. It’s not too difficult to imagine how this dynamic triggers the global proliferation of the most dopamine-spiking beige we’ve ever seen (yeah, I know that sounds like a contradiction in terms, but there is precedent: sugar has been added to everything now, despite its comparatively poor nutritional profile. Why is that, exactly?). And it is possible that over time we become accustomed to that new and kinda-sucky standard, and even start to think of it as excellent. Meanwhile, the diversity and depth of aesthetics made possible by the human mind and hand fade from memory.

In a similar way, it is also conceivable that a simulacra of intimacy thanks to a personal AI companion who can mimic empathy or flirtatiousness may also be satisfying enough for many. It’s the same dynamic that enables some people to view fast-food as a good enough substitute for real, nutritious food. Worse still is that the dynamic is compounded when the mediocre products of this system become so ubiquitous and cheap that other options begin to disappear or become unattainable (such is the nature of the urban food desert). Over time, and sometimes through no fault of our own, we can become acculturated to an impoverished human experience. With enough exposure and scarcity of alternatives, it just becomes like water to the fish that swim in it.

The second dependency, and perhaps our greatest defence against sliding into this beige hellscape, is that creatives and artists continue boldly to carve out and occupy the spaces where no machine can reach, to create art that is unmistakably ensouled, that carries with it all the hallmarks of having been made for an embodied entity and made by an embodied entity. We know these works when we experience them, because we experience them not as a sugar-rush, but as an intimate invitation into states of mind and ways of being that may have been previously hidden from our view. We know them also because they are the works that reach our hearts. Once we experience them, we are forever changed.

I cannot say for sure, but the intuition that I try to carry with some humility about this subject is that AI will only ever be able to, at best, simulate aspects of human intelligence. To the extent that I understand this intuition at all, it is partly because I don’t believe the human creature is reducible to machine-like processes. I believe the machine metaphor is an idiosyncratic one born of our strange, industrialised age. The very fact that we know AI does not experience understanding—which happens to be meaning of the original Latin word for intelligence—and that science and philosophy remain no closer to a complete explanation of consciousness itself serves to reinforce my intuition (who, after all, is the ‘I’ that understands when we say ‘I understand’, and is the ‘I’ therefore necessary in order for there to be understanding at all?).

That said, depending on one’s goal, a simulation of the real thing may be adequate for some purposes. A machine-made flat-packed coffee table has a place in this world. Viewed only through a narrow utilitarian lens, that table serves no lesser purpose than a table carefully handcrafted by a skilled human cabinetmaker. But if asked to consider their relative value in a holistic sense, I doubt many would seriously draw equivalence between the two. The former may deliver us convenience and some fleeting enjoyment, for sure. Yet a commissioned piece of handcrafted furniture in which the maker’s artistry, skill, and thoughtful attention to form and function have been physically instantiated may cause us to experience the object differently. I, for one, treat such an object differently, perhaps because I can sense the intention and intelligence of its maker. It’s something I’d want to pass onto my children for them to also experience and savour.

On the other hand, I do not have anything approaching this experience with my flat-packed self-assembled coffee table. I mean, I like it. It’s fine. My friends think its fine, too. It’s good enough, especially because its price tag was a small fraction of the artisan-crafted table. And therein lies the very temptation that paves the way to the flat-packing of the entire human experience.

AI may be a threat to industrialised labour and creativity. Yet it is also an invitation to re-examine what it actually means to be human. That invitation, should we choose to accept it, may see us rediscover and reintegrate those parts of human intelligence that, for many of us, were marginalised during our assembly-line education or which were burned away as part of our professional acculturation. Relational intelligence and the ability to cultivate connection and nurture intersubjective spaces. Deep cognition, including metacognition, and the kinds of intuition, wisdom and creativity that arise from being a complex embodied being. And moral agency, the ability to imagine conditions more aligned with goodness, truth and beauty, and to choose at every juncture to orient ourselves toward them. I suspect it will be these faculties and others that will be in demand—and most undisplaceable—in the age of AI.

‘In the past, jobs were about muscles. Now they’re about brains, but in the future, they’ll be about the heart.’

Minouche Shafik, president of Columbia University.

*Note: what human intelligence is exactly can hardly be done justice in this short post, and will be the subject of other posts by me in the future. But suffice to say here that human intelligence includes the unconscious, which we might infer as being responsible for the overwhelming majority of human cognition - 11 millions bits of information processed per second in total versus the mere 40 bits of information processed per second by the neocortex. This is a fraught subject alone, to say nothing of the relationship between consciousness itself and human intelligence.

Great post, James.

On the (thorny) subject of the unconscious, there aren’t many people who have researched and written about it more than CG Jung. I’m now immersing myself into Slater’s “Jung vs Borg” (and related) to understand more about the Jungian perspective one could (and perhaps should!) take when thinking about AI, for whatever is worth.

I'm of the view Natalia that humans lack wisdom at any real level. We're smart enough to make things that can kill us, but not wise enough to build in to those things, ways to stop them from killing us